Memories of the border zone

Various scenes from life during the Soviet era, as remembered by Gunārs Anševics, a writer, prose and poetry author, while living in the border zone.

In Russian times, you couldn't just go to the sea whenever and wherever you wanted. On the Great Sea side, opposite each village, there was a certain strip of a few hundred meters long, outside of which you were not allowed to appear. The time was also limited: from May to early October, from nine in the morning to ten in the evening.

It often happened that, having come from the hay meadow, tired and sweaty, people wanted to cool off in the sea, but – too late! – they were not allowed. However, I never looked so carefully. It happened that the soldiers missed, but if they did, we tried to explain what was the matter, and often we were able to come to an agreement with them. But, oh, how powerful the border guards felt at that time, and how humiliated the local villagers felt! This incident is evidence of this.

Once I came to Mazirbe with a goat, took it on my chest and drove along the forest road to the house. At the border guard post outside the fence, several soldiers were digging a large hole, and the commander himself, the major, was also hanging around there. He was a Latgalian, knew Latvian well, but spoke it only exceptionally. I was in a good mood, and an idea came to my mind. I choked the goat, tied it to the side of the road by a pine tree and went to the greens. Having approached the major, trying to take some kind of military stance, but still staggering under the influence of drunkenness, not very skillfully blurting out a few Russian syllables, I reported: "That-varishch, major! Razreshiķe obrakhitsya!" The soldiers all turned as one and looked, tell me, what is that drunk private doing here? In a slightly plaintive (specially staged) voice, I told the officer in Russian that I had a rather serious skin disease, that it was good to treat it with sea water, but, well, the season would soon end, and I wouldn't be able to go to the seaside anymore, but it would be so good to bring a bucket home from time to time... The major listened to me carefully, pushed his hat higher, folded his hands behind his back, and, noticeably unhurriedly, told me to walk back and forth, as if thinking about something important and repeating to himself more than once: "Well, what are you stoboi poļelaješ!" Finally, he had made the decisive decision and asked in Russian: "What was your last name? Oh, Anšević! Then, here, Anšević, as an exception, we will catch up with you and help you! You can go to the seaside at any time of the day. But next to the footprints left by soldiers, where they go for a walk, draw a capital letter "A". And with a slightly stretched out booted leg, he imitated the drawing of the letter. All this reminded me of the baronial times I read about in books and saw in films - if you asked the lord properly, he would often generously allow you.

I have had many dealings with soldiers, almost always in connection with taking my passport. Since this was a restricted area, there were often document controls on the roads. I have probably been taken off a bus about ten times, both in the restricted area and on its border. Each time I caused minor inconvenience to the other passengers, but especially to my relatives who were traveling with me. Nothing bad happened; while the border guards called and checked my identity, the bus waited for about five minutes before they let me go.

Once I found myself in an absurd situation, I was dropped off very close to my house, at Saunagas. At that time, some nasty young people who wanted to stand out must have happened to be there. Without further ado, despite the protests of the other workers on the bus, I and two others were put in a bobika and taken to the Saunagas police station. We were kept there for three hours, most of the solljuki were well known to me, because we often played volleyball and football with them. I felt almost at home among the choms, but I was still detained... Finally, after a few formalities, we were let home. It was a dark, late, rainy autumn evening. When we reached Pitragas, we were wet and soaked like shepherds, but one of our three still had to walk to Mazirbe.

When my daughter Sanita was three or four years old, we went to the seaside in the dark, late evening to secretly watch as border guards, who had arrived in a special car, slowly sent a very powerful beam of light over the sea. Suddenly, something rustled, a dog barked, and in the darkness of the night, against the background of the sea sky, two men appeared in a warlike pose with machine guns in their hands, a dog next to them. I guess the people who came really thought that the dog had bitten a border trespasser. A bright beam of light pierced the darkness, they took us to the car, I talked to the major on the phone for a while, I didn't have to go to Mazirbe just because I had a child with me... I was told never to do such things. In the dark of night, people with guns... everything can happen in a hurry and in fear.

I have never in my life deliberately tried to get into risky situations, but not taking my passport with me was an exception. Unless I absolutely needed my passport, I almost never had it with me. On the workers' bus, where documents were often checked, but usually I was not allowed to sit outside, everyone already knew: when the soldiers got to Gunārs, a bigger or smaller fuss would start, because he would not have documents... For me, although childish and boyish, it was still a kind of rebellion against this stupid, humiliating system: I am a local, my ancestors have lived here for centuries, and I have to show my passport to some foreign occupier at every step! It was a kind of stubbornly unyielding defiance and pride - I don't have my passport with me, and that's it! I never got tired of this game, and moreover, the further I went, the more I liked it.

Newspaper "TALSU VĒSTIS" September 16, 2006 No. 8 - sent by Inese Roze (Talsu region TIC)

Related timeline

Related objects

Mazirbe border guard tower

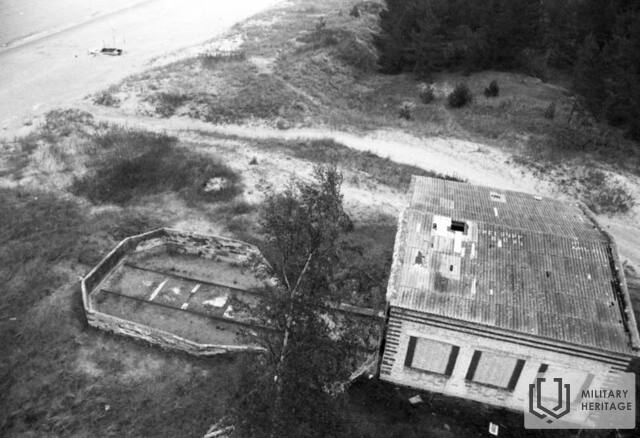

The Soviet border defence post was located in the building that used to be a maritime school, and next to it is a well-preserved Soviet border guard watchtower. The second watchtower is located right on the shore next to a parking lot. These watchtowers are a reminder of the Soviet occupation and the times when Mazirbe was a closed border area and civilians were allowed on the shore only in specially designated places and only during the daytime. This border guard watchtower is one of the best-preserved objects of its type on the coast of Latvia. However, it designated is dangerous to climb it.

Mazirbe Nautical School

The Soviet Border Guard Tower in this complex is one of the best preserved of its kind on the Latvian coast. Unfortunately, the condition of the buildings is poor, there is a rifle loading/unloading site on the site, and a drive and fragments of trenches have been salvaged.

The Coast Guard post was located in the former Marine School building. In the post-Soviet period, accommodation was offered in parts of the buildings.

The second tower of the Soviet Border Guard is located about 400 m from the beach, but unfortunately it is in a state of disrepair. However, the Mazirbe boat cemetery is located not more than 500 m from the beach tower towards Sīkrags.