Deportations of Lithuanian residents

II WW2, IV Soviet Occupation

The deportations of the Lithuanian population (1940-1953) are one of the most tragic parts of 20th-century Lithuanian history, when the Soviet regime pursued a systematic policy of extermination of the Lithuanian nation. These deportations, planned by Joseph Stalin, were part of a broader Soviet policy of repression that affected all territories occupied after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact: the Baltic States, Western Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus, and part of Poland.

The history of deportations began in October 1939, when about 25,000 people, mostly Poles and Jews, were deported from the Soviet-occupied Vilnius region. In 1940, after the establishment of the NKVD and security institutions in Lithuania, systematic deportations of the population began. The Soviet authorities compiled lists of so-called "anti-Soviet elements", which included 63 categories of persons: former civil servants, officers, teachers, farmers and other representatives of the intelligentsia.

The first mass deportation began on the night of June 14, 1941. People were awakened from sleep and given just a few hours to prepare for the journey. The deportations were carried out by NKVD officers specially sent from Moscow, with the help of Red Army soldiers and local communist activists. The deportees were often robbed, abused, and the men were separated from their families and sent to camps. During this deportation, 17,600 people were deported, of whom 71.6% were Lithuanians, 12.5% were Jews, and 11% were Poles.

The conditions of the journey to exile were inhumane. People were transported in animal-drawn wagons for 3-4 weeks. The wagons were equipped with wooden bunks for people to lie on, and in the middle was a hole for natural needs. The wagons were overcrowded, there was a lack of air, water, and medical care. Food was provided only once a day. Most traveled in summer clothes, because they did not have the time or opportunity to take warmer clothes. Weaker deportees - the elderly, children, and the sick - often died on the journey.

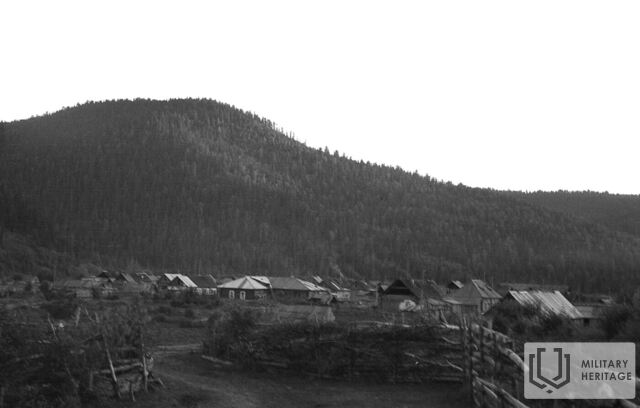

The exiles were distributed throughout various parts of Siberia: Komi, Altai and Krasnoyarsk Krai, Irkutsk, Tomsk, Sverdlovsk regions, and the Buryat-Mongolian Republic. Conditions were particularly harsh in Yakutia, beyond the Arctic Circle, where the exiles were forced to fish in the Laptev Sea. Many of them died in the first winter from hunger and cold.

Everyday life in exile was full of trials. The first exiles often had to build their own huts or barracks. They lived cramped, several families in one room, where the temperature dropped to -50°C in winter. The exiles worked in logging areas, mines, construction sites, and collective farms. The work quotas were unbearable, and for failure to meet them, their already meager food rations, which consisted mainly of bread and soup, were reduced. Forest produce helped them survive - berries, mushrooms, and fishing.

Children of exiles were often unable to attend school due to language barriers and discrimination, but Lithuanians tried to teach them their native language, history, and national identity. Despite the difficulties, exiles organized secret Lithuanian events and celebrations, sang hymns, and formed choirs.

After the war, deportations continued even more intensively. On May 22-23, 1948, 40,002 people were deported during Operation "Vesna", on March 25-28, 1949, 28,981 people were deported during Operation "Priboy", and on October 2-3, 1951, another 16,150 people were deported during Operation "Osen". The deportations were carried out in order to break resistance to Soviet power and accelerate collectivization.

The return to Lithuania began after Stalin's death in 1953, but it was a new stage of trials. The returnees did not have the right to settle in their homes, which were often already occupied by Soviet officials. They were forbidden to register in major cities, and it was difficult to find work, especially in their specialty. The children of the exiles faced discrimination in schools and when entering higher education. The KGB followed the returning exiles, they were considered "unreliable elements".

In total, more than 132,000 people were deported from Lithuania in 1940-1953, 70% of whom were women and children. About 28,000 people died in exile. According to Lavrenty Beria, a figure in the NKVD of the USSR, People's Commissar of Internal Affairs, and one of the main organizers of mass repressions in the 1930s and 1940s, the total number of repressed Lithuanians reached 220,000 - every tenth Lithuanian resident. By 1970, only about 60,000 deportees had returned to Lithuania, and about 50,000 were unable to return or returned very late.

In 1988, the deportees were officially rehabilitated, and in 1990, after Lithuania regained its independence, they were granted social guarantees and the right to compensation. June 14 became the Day of Mourning and Hope. However, Russia, as the successor state of the USSR, never officially apologized for the deportations and their consequences for the Lithuanian people.

The experiences and experiences of the exiles have become an important element of the historical memory of the Lithuanian nation, passed down from generation to generation through memoirs, diaries, letters and testimonies. The deportations not only physically destroyed a large part of the nation, but also damaged the traditional social structure, family ties and cultural heritage. It was a systematic policy of genocide, the consequences of which are felt to this day.

More information sources

Related timeline

Related objects

Plungė railway station

The railway station in Plungė was built as part of the Telšiai-Kretinga line, which was built by the Danish company Höjgaard&Schult. The construction of the station began in 1930, and the main works coincided with the great Plungė fire of 1931, which nevertheless did not stop the process. The station was opened on 29 October 1932.

The Plungė railway station was built according to a typical project, a similar station is located in the city of Telšiai. In the architecture, between the one-story side wings, a two-story central part with a vestibule inside stands out, and an outstanding aesthetic element is the openwork decor of the roof parapet, which is currently being reconstructed.

During the interwar years, the Plungė garrison soldiers' orchestra was popular in the city, which would accompany departing reserve soldiers home from the new station with music. It is recorded that on September 18, 1938, soldiers returning from field exercises were ceremoniously welcomed at the Plungė railway station by gymnasium and elementary school students, teachers and other townspeople.

During the Cold War, Plungė railway station also became important in the military industry. In the period 1960-78, the Šateikiai and Plokštinė forests were home to the Šateikiai above-ground and Plokštinė underground thermonuclear missile launch bases. Both during their construction and later, during the period of operation, construction materials, weapons and everything else were transported by train to the Plungė and Šateikiai railway stations.

During the mass deportations of the population to camps by the Soviet occupation authorities, in 1941-1952 a number of them were also deported from the Plungė railway station, as evidenced by a commemorative plaque installed on the wall of the passenger hall building. The plaque was unveiled on June 14, 1991, thanks to the efforts of the members of the Plungė group of the Lithuanian Reorganization Movement and the Plungė company of the Lithuanian Riflemen's Union.

Mazeikiai Railway Station

The railway station is located in the central part of the city of Mažeikiai, therefore it became the axis of urban development. It began operating on September 4, 1871, next to the newly built Liepaja-Romnai railway line. The passenger hall built in 1876 became the first brick building, around which the city gradually formed. A few years later, Mažeikiai (at that time called the city of Muravjov) was connected to Riga.

Until 1918, the station, like the city of Mažeikiai, was called after the Vilnius Governor-General Muravjov, nicknamed "Korik" and famous for suppressing the 1863-1864 uprising. Many historical figures visited the station: during the First World War, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Imperial Germany dined in the station's restaurant, where the Bermontin commander, Colonel Bermontas-Avalovas, was promoted to general, and in 1927, the President of the First Republic of Lithuania, Antanas Smetona, visited the station. Clashes between the defenders of Lithuanian freedom and the Mažeikiai Company and the Red Latvian Riflemen, who operated on the side of the Red Army, took place near the station.

In 1941 and after the war, residents of the Mažeikiai region were deported from the station. Among them was four-year-old Bronė Liaudinaitė-Tautvydienė (chairwoman of the Mažeikiai branch of the Lithuanian Association of Political Prisoners and Deportees) with her family and many other families.

Today, the station has not lost its original purpose, and a memorial plaque is attached to its wall, reminding of the 1941 and post-war deportations to the depths of Russia. Every year on June 14, the Day of Mourning and Hope is commemorated at the station.

Deportation train wagon

A restored deportation train carriage is located near Radviliškis railway station as a reminder of the tragic history of the mass deportations of the inhabitants of the Republic of Lithuania

to remote areas of the Soviet Union by the Soviet occupation authorities from 1941–1952. More than 3,000 people were deported from Radviliškis alone.

In total, approximately 135,500 people were deported from Lithuania from 1941–1952. On 14 June 1941 – the first day of mass deportations in Lithuania – train carriages began to be “filled” with the inhabitants of Radviliškis and the surrounding area.

In 2012, the carriage was handed over to Radviliškis District Municipality by the Vytautas the Great Special Operations Jaeger Battalion of Lithuanian Armed Forces with the mediation of the Genocide and Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania. The authentic deportation train carriage was brought from Kaunas and carefully restored by the railwaymen, and now it houses a small exhibition.

Kompozicija "Skausmo ir kančių kelias"

Šalia Radviliškio Švenčiausiosios Mergelės Marijos Gimimo bažnyčios medinės varpinės 1989 m. atidengta Trijų kryžių kompozicija „Skausmo ir kančios kelias“, skirta Lietuvos kankiniams, tremtiniams, politiniams kaliniams, žuvusiems Sibiro platybėse, atminti. Jos autoriai – V. Vaicekauskas, A. Dovydaitis ir E. Gaubas. 1995 m. birželio 14-ąją, Gedulo ir vilties dieną, šalia pastatytų Trijų kryžių pašventintas Skausmo ir kančios kelias – geležinkelio bėgiai, simbolizuojantys į tremtį iš Radviliškio žmones vežusius ešelonus. Iš lauko akmenų sudėta Atminties sienelė – paminklas negrįžusiems iš tolimųjų Sibiro platybių. Bėgiai sulaužyti, kaip ir ištremtų žmonių likimai. 2001 m. birželio 14 d., minint Gedulo ir vilties dieną bei tremties 60-metį, prie šio simbolinio memorialo buvo pasodintas Vilties ąžuoliukas.

Žeimelio evangelikų liuteronų bažnyčia

Žeimelio miesto centre stovi Žeimelio evangelikų liuteronų bažnyčia. Ji buvo pastatyta 1793 m., senosios 1540 m. statytos bažnyčios vietoje. 1753–1759 m. Žeimelyje kunigavo latvių rašytojas folkloristas kunigas Gothardas Frydrichas Stenderis, sukūręs pirmąją latvių kalbos gramatiką.

1929–1949 m. bažnyčioje tarnavo kunigas senjoras Erikas Leijeris, nacių ir sovietų okupacijų metais pagarsėjęs kova už bažnyčių išsaugojimą. E. Leijeris nepaliko Lietuvos 1941 m., kai beveik visi evangelikų liuteronų kunigai buvo pasitraukę į Vokietiją (veikė tik 8 parapijos iš 55), rūpinosi visos šalies evangelikų liuteronų parapijomis.

Sovietų okupacijos metais aktyviai priešinosi bažnyčių uždarymui, atkūrinėjo parapijas, skyrė į jas dvasininkus, protestavo prieš bažnyčių atėmimą bei kunigo Jurgio Gavėnio suėmimą. Pas save namuose nuo tremties slėpė generolo, Lietuvos kariuomenės vado Stasio Raštikio dukrą, prezidento Antano Smetonos giminaitę Meilutę Mariją Raštikytę-Alksnienę. E. Leijeris parūpino jai naujus dokumentus, pats užsiėmė jos švietimu, neleisdamas į mokyklą.

1949 m. gale buvo suimtas sovietinių struktūrų, nuteistas „už antisovietinę veiklą“ ir ištremtas į Krasnojarsko kraštą. Mirė 1951 m. Michailovkos lageryje, kapo vieta nėra žinoma. 1989 m. buvo reabilituotas.

E. Leijerio atminimui Žeimelio miestelio kapinėse pastatytas paminklas, jo vardu pavadinta gatvė, o bažnyčioje pakabinta memorialinė lenta.

Šiaulių geležinkelio stotis

Geležinkelio stotis įsikūrusi Šiauliuose.

1871 m. rugsėjo 4 d. atidaryta trečios klasės stotis, priklausanti Liepojos-Romnų geležinkelio linijai. Šiauliai tapo svarbiu geležinkelio mazgu. Per abu pasaulinius karus stoties pagrindinis pastatas – keleivių rūmai buvo apgadinti ir kelis kartus rekonstruoti: 1923 m. atliktas kapitalinis remontas, 1930-1931 m. rūmai išplėsti ir pertvarkyti. 1935 m. Šiaulių geležinkelio stočiai buvo suteikta I klasės stoties kategorija. Po Antrojo pasaulinio karo stotis vėl rekonstruota. Sovietmečiu 1971 m. rugsėjo 4 d. joje atidarytas geležinkelio muziejus. Stotis tapo SSRS vykdomų represijų prieš Lietuvos gyventojus liudininke: 1941 m. birželio 14-18 d. trėmimų metu iš Šiaulių buvo ištremta 351 šeima ir pavieniai asmenys, trėmimai tęsėsi ir 1945-1953 m.

Šiandien stotis tebeveikia, ant jos pastato sienos 1996 m. atidengta atminimo lenta tremtiniams (po 2010 m. atnaujinta).

Related stories

Mokytojos Rimtautės kelias į Sibirą

Just two months after their wedding, teacher Rimtautė Jakaitienė was exiled to Siberia, along with her husband and his parents. Without trial, without charges - simply for being family.

A nine-year-old's journey into exile

Writer Regina Guntulytė-Rutkauskienė, who was exiled at the age of nine, remembers the deportation of June 14, 1941, when she and her family were taken to Siberia. Her story reveals not only the physical but also the emotional pain of exile, which accompanied her even after returning to Lithuania.

Women's work in Soviet exile

Lithuanian exiles, accustomed to traditional female roles in interwar Lithuania, faced hard physical labor and a new reality in exile, where there was no longer a distinction between "male" and "female" work.