From Ádolfs Ers' book "Vidzeme in the Struggle for Freedom" about the refugees' journey in Valka

Starting from the time of the refugees, Valka was given a more important role than other cities in Vidzeme, because it was home to the politically active newspaper “Līdums”, where Latvia’s spiritual and political weapons were forged, and also because it was a crossroads where roads from three sides of Latvia converged: from Riga, Alūksne, Mozekile, and also from Estonia and Russia. It had connections with refugees from all sides – Tartu, Pliska, Moscow and St. Petersburg. There was a large refugee center here.

The people save the living force

Page 18

In the dark times, when the German invaders stopped between Jelgava and Riga, and near the Daugava, when all of Vidzeme was a refugee camp, a group emerged among the nation's leading intelligentsia that decided to stand on Latvia's northern border and ensure that the Latvian people did not drown in the vast sea of Russia.

Northern Latvia, with Valka and Valmiera, became a flood protection wall for refugees.

Page 19

The largest Latvian economic organizations – the Latvian Agricultural Central Association and “Konzums”, as the front strengthened near Riga, evacuated from Riga, but did not travel to Russia and settled in Valka.

The network of refugee committees spread throughout Vidzeme and Latgale and also to Russia, where many refugees had already managed to leave. The refugee committees were like warm nests for a wandering people to rest. Here, relatives and neighbors, who had been scattered in cities and villages by the hasty departure from their homeland, communicated and met. Communication offices and newspapers brought the separated together. The Latvian language, which was the only language for many, was heard in the refugee committees. They maintained Latvian schools, provided clothing and food. Extensive social activities also took place here: uniting the people in one community and forming political ideas. The dusty carts from the Vidzeme highways, which were short of bread, stopped at the doors of the committees. Those who did not have housing were also provided with that. The committees took care of all the needs of the refugees. During its stay abroad, it provided great moral and material support to asylum seekers who had been driven from their homes. Funds for this work were provided by the public in the form of donations and by the government.

During the time of the refugees, Valkas and Valmiera became Latvian spiritual and economic centers. Newspapers were the spiritual reinforcements for the Latvians who had gathered in Vidzeme and who had been scattered in Russia.

Page 20

The greatest importance at this time fell to the newspaper "Līdums", which, together with the Central Society and "Konzums", moved from Riga to Valka. "Līdums" expressed a certain national patriotic idea, which was cherished by the majority of the Latvian intelligentsia. At first, it mentioned Latvia as an autonomous part of Russia, but later spoke out for an independent Latvia. The Central Society of the Great Peasants' Organization and "Konzums" were willing to make all possible sacrifices for the preservation of Latvian material and spiritual culture and also for the strengthening and fulfillment of national ideas. Their leaders understood the fate and needs of Latvians. Among them were such men as K. Ulmanis, V. Skubiņš, P. Siecenieks, E. Bauers, V. Siliņš, Ed. Laursons, J. Blumbergs, etc. leaders and employees of these organizations. Almost the entire national intelligentsia that had left Riga gathered around “Līduma”, the list of its contributors included the names of all the Latvian writers, poets, artists, publicists, agronomists, scientists and politicians of that time; they were J. Akuraters, A. Austriņš, E. Bauers, J. Ezeriņš, E. Frievalds, V. Gulbis, J. Janševskis, Alfr. Kalniņš, A. Ķeniņš, K. Krūza, A. Kroders, J. Lapiņš, L. Laicens, Z. Meierovics, V. Plūdons, P. Rozītis, V. Siliņš, K. Skalbe, V. Skubiņš, K. Ulmanis, Ed. Virza, E. Vulfs, etc. The newspaper was managed by editor Oto Nonācs. As an experienced journalist, Latvian patriot, and far-sighted politician, he knew how to interpret the thoughts of the leaders of Latvian material culture and find harmony between them and the ideologists of spiritual culture.

Page 21

That is why the best harmony always reigned between the publishers of “Līdums”, who were also the leaders of the central society and “Konzums”, and the collaborators. “Līdums could confidently speak about the matters closest to the Latvian heart, and as the only newspaper widely distributed on Latvian soil at that time, it acquired a leading role.

Page 22.

The importance of Valka at this time will always be remembered when talking about the creation of Latvia. Not only the intelligentsia from Riga, but also the local people participated in the implementation of important national ideas. Northern Latvia was prepared for the patriotic struggle before, when in the borderlands, especially in Valka, there was a competition between Estonians and Latvians for national superiority in the cultural and economic fields. For thirty years, cultural work had been carried out here in societies and the fight against the Germanism of the Willows had been waged, as well as the economic balance between Latvians and Estonians had been maintained. Valka became particularly active in public life around 1905, when the Relief Society was founded and the Valka newspaper “Kāvi” was published.

During the war, the population of Valka increased from 18,000 to 30,000 due to the influx of refugees. At one time, Valka was home to the Cimze Seminary, which also had an impact on the spiritual life of local Latvians.

At the beginning of the war, Valka was already a strong cultural stronghold in northern Latvia.

Page 23

The wave of refugees made it the main center of all of Latvia, from which Latvian patriotic thought radiated throughout Vidzeme, Kurzeme, and also Latgale.

Starting from the time of the refugees, Valka was given a more important role than other cities in Vidzeme, because it was home to the politically active newspaper “Līdums”, where Latvia’s spiritual and political weapons were forged, and also because it was a crossroads where roads from three sides of Latvia converged: from Riga, Alūksne, Mozekile, and also from Estonia and Russia. It had connections with refugees from all sides – Tartu, Pliska, Moscow and St. Petersburg. There was a large refugee center here.

The Valka Refugee Committee fed about 600 people every day at its food service, at first it issued refugee identity cards without interruption, organized communication between refugees' relatives, furnished apartments, took care of the sauna, established a reading table, a medical center, a job office, etc. The Refugee Committee was founded by the Relief Society, and later it became subordinate to the central committee.

However, the plight of the refugees was so great and widespread that it was not possible to help everyone. Many refugee families lived in the forests in canvas tents and carts until late autumn in the first year, without receiving any help. There were those who considered it beneath their honor to ask for any help.

Page 24

With the refugees came large herds of cattle. The requisitioning commissions bought them for the needs of the troops, but there were so many cattle that even the commissions were unable to take them. The forests and roadside fields were filled with hungry cows, because the roadside fields could not feed all the cattle, nor could the grass grow after it was plucked or trampled.

Life in Valka

Page 26

Although Valka had already become the leading center of the unoccupied part of Latvia, Vidzeme and partly Latgale, before the revolution, life here went on relatively calmly and slowly, with a hint of the rear of the front, even peacetime, the sound of cannons rumbling between Riga and Jelgava and along the Daugava, echoing like distant thunderclaps, all the way to the Seda forests on the Estonian border. The town knew the war only from these distant rumblings and newspapers. The flood of refugees had already subsided, they were placed in shelters and at work, committees took care of them.

The apothecary brewed medicine as he had for twenty years, the slender chimney of the flax factory smoked like a cozy cigar, you could get lunch at the society. The Relief Society organized a choir and orchestra from the refugees and performed oratorios in the Lugaži Church, and actors who had fled to Valkas organized performances at the Guest Society.

Page 27

Only the windows and shelves of the shops were empty and everyone bought food from farmers on the Latvian Lugaži market square, or at the Russian church, where the dominant language on market days was Estonian. However, there was still bread for everyone. Every evening on Kungu Street, two men turned the printing press wheel, and newspaper pages with the headline “Līdums” fell out of the machine. Work in the editorial office went on as usual, connected with the life of the poor in the town, but also with tense attention to the war front, the plight of refugees and the Latvian riflemen. The newspaper carried this attention and the associated intuitions about the fate of the Latvian people and land to refugee points in Latvia and Russia, to homes, dugouts and records. The intuitions matured at congresses and meetings to turn into thoughts and will.

These congresses were the first, still hesitant, but heroic messengers of the Latvian state. “Līdums” carried the decisions of the congresses to the people.

The newspaper's editors all sat around one table in a house on the corner of Kalēju Street and prepared manuscripts. With this, they also forged the Latvian state: the majority of the population accepted the cherished idea of independence. The layer of conscious nationalists grew.

Page 28

The editors worked all day in the editorial office, from where the editor-in-chief O. Nonācs did not leave, concentrating on the manuscripts through the lenses of his glasses. In the morning he told the other editorial staff what had been decided yesterday at the publisher's meeting about refugee affairs, the newspaper's direction, and the Riflemen. After that, the sub-editors had to get down to translating telegrams and compiling local news. Editor O. Nonācs wrote the introduction for tomorrow. In the editorial office, he was the main introduction, only K. Skalbe occasionally tried his hand at this field. Later, he was joined by the young gifted journalist cand. jur. Edm. Freivalds, who had arrived from St. Petersburg. When Antons Austriņš also sat down in the editorial office, he said that the newspaper should provide some significant literary work, at least from classical literature; he mentioned Cervantes' Don Quixote. The editor agreed. I became the translator of Don Quixote. I also had to proofread and write a report on the front, pinning flags on the map that marked the front that was being advanced, broken, or pulled back. You could tell by the flags what would happen to the front in the coming days: if the “bag” was bent somewhere, then the wings would definitely retreat. The predictions also came true. Local correspondents and collaborators came to the editorial office with their articles. There were not many of them. The commission secretary brought explanations on the issues of wartime, the teacher brought philosophical articles, the student who has now become a lawyer brought legal ones, the city secretary brought the latest decisions of the city council and market news, but the poor man Mednis wrote about the unbearable country roads.

Page 29

One night, a German zeppelin flew over Valka, flying on a railway bomb, but none of the bombs hit their target. One fell into the yard of a house and killed two women – a mother and daughter. Panic reigned in the city all night and the next day. The city with all its houses would probably have fled, but impossibility left everyone in place, and life went on peacefully again, as if there was no rear of the front. The readers knew what was hidden in the lines of the newspaper's editorials. These were thoughts about Latvia.

Soon after, painters arrived from the front: Strunke, Ubāns and Tone; Suta from Russia. They were soldiers, perhaps more soldiers than painters at that time; Suta brought Cubism from Moscow. It was new and unprecedented, the town talked about it when Suta gave a lecture at the Latvian Society.

Once, a slender, portly officer from St. Petersburg came to the editorial office, bringing important news. He spoke slowly and thoughtfully, seemed more of an aristocrat than a peasant. He lacked Latvian sincerity and simplicity. He was no ordinary person. The editor took him into his apartment. When he came out, the officer shook everyone's hand and left.

“Meierovics,” the editor explained, “from St. Petersburg, in refugee affairs.”

"A great similarity, but also a difference with the rustic Ulmanis. A certain personality," Austriņš added.

“One is the city, the other is the countryside,” said a member of the editorial staff.

Page 30

Now and then, agronomist Kārlis Ulmanis also came to the editorial office with articles related to saving the people from extinction in Russia, about the support of refugees, about political organization. But among the large articles, he also brought short notes about cleansing the Latvian language of Germanisms and Russicisms. From the new words he designed, the envelope instead of “konverta” has gained existence. Maybe others too, I don’t remember. He encouraged writers to write about contemporary events. Contemporary events of that time are only now being included in writing, because back then they seemed too close to be formed into artistic images.

When a new arrival wandered into the editorial office, it seemed like a warmer wind had turned. After that, everything went back to normal.

People in Valka were hanging out together, wanting to meet, talk, hear something new. The editorial staff and people close to them would go out of town on Saturday evenings to the Ruķeļi landlord Jānis Pavlovičs. He lived a couple of kilometers from town among vast cabbage plantations and apple trees. Skalbe enlivened these evenings with political conversations, Austriņš with songs that could be heard through the wall.

Page 31

Once, the current Prime Minister Kārlis Ulmanis also came. At that time, there was still no idea how Latvia would be formed, whether it would have autonomy or independence, but long discussions already broke out about Latvian money, the importance of the railway in the Latvian budget, agrarian reform and the division of estates - with or without compensation.

Two days later, the Valka community and neighbors rushed to the Valka Savings Bank hall. There Ulmanis gave a lecture about his experiences in America. The speech revealed things unprecedented in Latvia, American habits, ways of working and great devotion to work, when work is like an end in itself, like holiness. The speaker's humor alternated with seriousness, he could not stand still and walked while talking.

Soon after the revolution opened the way for free organization, an important meeting was held in the same room, attended by about 200 delegates from 17 places. It was the founding meeting of the Latvian Farmers' Union. The meeting was chaired by Kārlis Ulmanis. It was the first such extensive organization of Latvian farmers in the life of the Latvian people. The union could already boast 1,500 members. The meeting took place on April 29, 1917. The new organization, headed by K. Ulmanis, became the most important organizer of the Latvian state, and later it was also the leader in important state issues.

Already earlier, new times were felt in the air. And, indeed, new, important events were coming soon, but no one predicted the outcome.

Page 32

The rumble of revolution began on the battlefields. Behind the front, including in Riga, congresses and meetings spoke and wrote resolutions, some proclaimed peace until final victory, others – peace without annexations and contributions.

Valka was not worried about it yet. The newspaper's work was going on as usual. The city secretary brought a report on the city council meeting to the editorial office. The owner of Ruķeļi brought an article with good political ideas. He had met the agronomist Ulmanis, who had received good news from Riga, that regulations had been issued there on the termination of requisitions. But then a rifleman from the Riga front came to the editorial office. He was convinced that something was no longer good at the front. Soldiers were not showing honor to their officers, discipline was breaking down. Soldiers were talking about the betrayal of their officers, but themselves were fraternizing with the Germans. There were also agitators in the Latvian regiments who said that the bourgeoisie should be wiped off the face of the earth, and that workers and soldiers should receive power by electing councils.

“We need to prepare for serious things, something will happen,” the archer said.

“The farmers will also have a name,” the editor expressed his silent thoughts, looking through his glasses at the window, where February snow glittered on the roof.

Something important was brewing. Another layer of the people was growing, next to the national one. It did not mention the word people and knew only two words: bourgeoisie and proletariat.

Page 33

It heralded a dispute, even a bloody struggle, between two layers: the national and the international.

It was not noticeable when worn. The telegraph probably didn't know anything about the two layers.

"Everything is in order," he reported from the front and from life.

But soon, like a zeppelin bomb, Valka was also shaken by the news that the Tsar had abdicated. The rallies roared: Svaboooda, freedom! Prrrāvilno, right!”

When the editor tore open the telegram about Nikolai's resignation, March snow began to appear on the roof outside the window. The editor had no time to see it now.

“That's it,” he handed the telegram to the translator: “Now go away.”

Joy shone on the faces of all the editors. There was no doubt that Russia would collapse without a tsar. But Germany? No one doubted that Germany would be defeated on the Western Front. Then the sacred time, awaited for hundreds of years, would come for Latvians, when they would be able to say “Now Latvia is free!”

Page 35

The second large congress was held in Valka, a congress of public organizations. Here, Miķelis Valters declared the principles of the Latvian state with such solid projects as the Latvian parliament and money. At the time, this seemed too far-fetched to many.

These congresses were the first dubious, yet confident messengers of the Latvian state. Their resolutions found a response among the people, although the Bolshevist rallies' speakers scolded those who spoke the name of Latvia, and their whistleblowers would not let them speak.

In the turmoil of the revolution

Page 36

"A new era has come," the first speaker began his speech in the hall of the Union Society: "We, Latvians, will now be able to shape our own government and culture according to our own mind and advice, without listening to the minds and advice of others..."

The audience applauded, but one whistled. It was not a spring thrush, but a young man with an ironic smile. He did not wait for the first speaker to finish, but climbed onto a chair and said that the speaker was blowing blue mist into his eyes. Not to listen to the counter-revolutionaries, but to come the day after tomorrow to the great people's meeting, which would take place in Lugaži Square. There he would hear the truth about the goals of the revolution and the current moment.

The audience watched and wondered: who is he?

"Iskolat," someone whispered a strange, unheard word.

The town sewed red-white-red and blue-black-white flags, even the firefighters and the social society unfurled their dusty flags and went to the hill market square, from where a procession through the city to Lugaži Square in honor of the revolution had been arranged. In front of the hill market, red flags, with which the soldiers had come, were already fluttering. A forest of flags was forming, and each had its followers: the society flags were for the members of the societies, the Latvian flag for the Valka Latvians, the Estonian flag for the Estonians, the red flags for the soldiers and the workers of the flax factory. The fire brigade orchestra marched ahead of the procession, exhaling the Boer March from its round cheeks.

Page 37

The red flags were followed by a private orchestra, playing the Marseillaise alternately with the Radetzky March.

The procession's tail grew at every street intersection: the curious joined in, wanting to see and hear something, let it be something, and those who, without invitation, felt joy at the overthrow of the Tsar. The river of the procession flowed into Lugaži Square, shaking the entire city. The speeches began.

Everyone wanted to say what was on their minds, but not everyone succeeded.

The first to step onto the podium, which was made of empty boxes of goods, was a representative of the local government and spoke about the great significance of this holiday. Once upon a time, an usurper had been overthrown and freedom was coming, which both Latvians and Estonians would gain in their autonomous states. The speaker spoke at length, but did not say much more. That was the gist of his speech.

The speaker from the previous evening, who promised to reveal the truth about the current situation and the goals of the revolution, took the podium second, after the first had been applauded and shouted: “Right!” Hurray!”

The next speaker was so young, that's probably why the speech came out so flat:

Page 38

“Comrades! Even back then, when I was languishing in prison,” he began his speech: “the proletariat organized itself to fight the autocracy. Comrades! So to speak, proletarians, you, for example, who languish in basement apartments, so to speak, you masses of workers, who are being sucked out by the capitalists and bourgeois, cultivate your class consciousness and, so to speak, let us fight the counter-revolution, so that the working class would be the only class that stands, so to speak, above imperialism and on revolutionary class foundations. Long live the masses of workers! Down with the bourgeois. Long live the revolution!” “Prāvilno” responded at the rally, “hurray” as if going into a bayonet attack.

Then the representative of the local society took the stage. He was not a great speaker either, but on a solemn occasion he had to speak.

"My lords and my ladies. The revolution has taken place. The Tsar has been overthrown and the autocracy is over with Raspukhin. The revolution is also over. Now it's time to get down to creative work..."

“This is just the beginning!” he was interrupted by a soldier standing next to the previous speaker.

“Yes, the fight for Latvia begins,” the speaker continued, gradually warming up: “The time has come for Latvians to free themselves from guardianship, to stand on their own two feet. We must stand as one man to reach the ideals that Kronvalds, Auseklis, and Valdemārs have already fought for. We must think about a Latvia that would belong to Latvians, but not to everyone else...”

Page 39

There were shrill whistles, followed by cries of "Enough!" The noisemakers were stationed in various places. They did not stop until the speaker had left the podium. Then the floor was given to the representative of Iskolastrel.

He spoke of an international that would bring world peace and bread for all. He too punished the capitalists and cursed the counter-revolutionaries. His speech also ended with shouts of hurrah.

When the soldier – nationalist Rudainis – climbed onto the box, the air was already saturated with the sounds of the Internationale, which the orchestra played after the speech of the Bolshevik representative.

Rudainis began his speech with the words: “Free citizens! National goals...”, but he couldn’t go any further because someone shouted “Down with the citizens, long live the workers!” and people in soldier’s coats joined in the melee: “Right! Rule!”

“Let them speak, let them speak!” shouted the citizens' supporters.

Then such a flurry of shouting began that no one could speak. The shouting turned into screams and threats. Fists were raised in the air. The audience was afraid of a fistfight and began to disperse. Then the firefighters were the first to roll up their flag and leave. The same thing happened with the other flags, only the red one remained, but then there was no audience left, except for soldiers' overcoats and a few private shouters and whistlers. The celebration ends with less celebration than it began. The private orchestra with the Marseillaise marched into the house.

Page 40

The thoughts of the people were no longer one thought. The representatives of two directions, the nationalist and the internationalist, each with their own convictions, walked the streets of Valka. When they met, they looked closely into each other's eyes; wanting to read there the answer to the question: are you not an enemy? Are you not a traitor to the cause of the people?

They each had their own truth. One dreamed of an impossible brotherhood of nations, the other of the brotherhood and existence of his own people. One was supported by organized cheers and whistles in Lugaži Square, the other mentioned the silent thoughts of the people, which the shy people of the peaceful town considered inappropriate to defend with shouts and whistles and went home to wait for their time, which could not fail to come.

Page 41

Each had their own companions.

After the Tsar's abdication, a turmoil called a revolution began. It disrupted the troops and the front.

Page 42

The war ended and the time for talking came. Rally after rally came. Rallies were held in squares, in community houses, and in churches.

National organizations, newspapers, and municipalities were liquidated by the international “Iskolat” – the Bolshevik executive committee.

The Latvian regiments were not only composed of Bolsheviks. They founded the National Soldiers' Union, whose leadership also arrived in Valka with the revolution and settled opposite the post office with its newspaper "Laika Vēstis", which bravely fought the communist "Cīņu" and the Iskolat "Brīvos Strēlniekus" until it was closed down, just like "Līdums". The leaders of this newspaper were A. Plensners and A. Kroders.

The nationalist soldier, seeing that the army was falling apart, did not return to the front either, but remained in Valka, joining the National Union of Latvian Soldiers, whose purpose was to keep Latvian soldiers together, to prevent them from leaving with the Russians and Russia, and to use them as an armed force for the establishment of the Latvian state. The National Union of Soldiers moved to Valka from Cēsis.

Page 43

“Laika Vēstis” held to a certain national line. This was a thorn in the side of the bigots. “Laika Vēstis” called for joining the National Soldiers’ Union and defending Latvia, independent of Russia. The spirit of the newspaper was about the same as “Līdumam”, only with a more militant tone.

"Housing crisis," said a resident of Valka.

The influx of soldiers made this word resonant. The words were also spoken – apartment requisition. Headquarters and councils requisitioned premises. The inhabitants had to huddle together tighter.

The editorial staff member was satisfied, having received a room on Semināra Street with such low ceilings that the poet Antons Austriņš had to bow his head when entering, and with such low windows that one could see the boots of passers-by in them. The most noticeable crisis was the housing crisis. On Fridays, writers, artists and their friends gathered at the editorial staff member's place to read new poems and discuss political news. Austriņš, a lover of old Latvian traditions, called the evenings Friday evenings. Here K. Skalbe, E. Virza, A. Austriņš, J. Akuraters, A. Plensners, A. Kroders, Pāvils Rozītis and others read their works, here he saw the painters Strunki, Toni, Ubāna, Stender, who played the violin, and the conservatory member H. Kozlovska, who had come from Pēterpils, sang the unheard Latgale song. Here, one could also see the Cēsis residents J. Grīns, A. Bārds, and the Terbatis residents V. Dambergs and Jūlija Roz.

Page 44

Rifleman Rudainis stayed with an old acquaintance in the small house of the Seminar, where a dairy instructor who had fled from Kurzeme also lived, now earning a living by filling cigarettes and selling them at local newspaper kiosks, and at the other end of the house a master of various fine iron products – a mechanic. When writers and artists came to the editorial board member, Rudainis could also be there. He had to be surprised and ask that there was not a single supporter of “Iskolat” among them. Here, all the defenders of Latvian independence.

Rudainis found certainty and clarity for his convictions here. He realized that now all Latvians should stick together, because the time had come when, united, they could even gain their independence.

One evening, walking past St. John's Church, he saw lights in the windows. What could a church service be like during the Bolshevik era? He thought and went to see what was happening in the church. The church was full of people. An internationalist stood in the pulpit and, raising his hands, just like Pastor Kupčs, gave a campaign speech. Soldiers and privates sat in the pews. The path through the middle of the church was also filled with listeners. Entering, Rudainis took off his hat, as in church, but, stopping in the middle of the church, he saw that everyone was wearing hats, just like in a synagogue. Here a hand took the elbow of the newcomer.

Page 45

"Comrades, put your hat on! Aren't you so bourgeois that you're not wearing a hat?"

It sounded like a mockery of someone shouting on every street corner: “Sbobo-oo-da”! Freedom!”

The internationalist spoke about the bourgeoisie and the united front of the world proletariat, which was about to be established: “They, so to speak, live in palaces, and you in basement apartments. They send you to die in the trenches, just as, so to speak, your brothers were sent by William II. Down with the war! Let us end it and give our German brothers a hand over the trenches. Then they too will lay down their arms. We will fraternize! Long live fraternity!”

“Pra-ra-rave!” sounded in the church.

Now, comrades, you will see that the French, English and American proletariat will join us, the black colonial troops who are shedding blood on the Western Front will join us. The proletariat will, so to speak, conclude a peace for all time. It will be a peace after which nation will no longer rise against nation, brother against brother, comrade against comrade. There will be no nations, there will be only the proletariat...”

Rudainis did not understand why there should be only a proletariat, why there should be no people, and he also did not believe that the Germans could be such loving brothers to the Russians.

Page 46

Soon after, Rudainis, walking past St. John's Church, saw another scene - a group of peasants with bundles and pillows under their arms entered there, accompanied by soldiers. The residents said that a concentration camp for the bourgeoisie had been set up in the church. Did these peasants come from those castles that the bourgeois destroyer had recently spoken about in the pulpit? There were no castles or basement apartments in Valka. The church was full of peasants, pharmacists, priests... A priest and two Smiltenai farmers were shot on the way to Valka and left on the edge of the grave.

The Valka resident silently shook his head: what else haven't we experienced?

Having come home from St. John's Church, Rudainis met his friend and Antons Austriņš, correcting reports and poems brought from the editorial office. A moment later, the poet E. Virza rushed in, took off his rifleman's overcoat and took a clumsily folded piece of paper from his pocket.

“Listen to what I wrote,” he said, “pushing his slipped nose pin closer to his eyes.

Holding a piece of paper in his hand and raising it above his head for a moment, but not looking at her, Virza recited his newly written poem "A Dream on a Winter Night":

Page 47

I had a dream - it wasn't all a dream.

On the tower, huge, which was ghostly and old,

I was climbed and what the eyes see

Only when they are closed in sleep,

Immersed in the music of the rhythm, the beauty of the rhymes, and the brilliance of the paintings, the poet continued to recite the devastating poem "Iskolat", ending thus:

"Then the noise subsided, and everything trembled."

The beast had burst from excessive inflation.

There was such a smell around that it made me feel sick to my stomach.

I closed my eyes from the sudden fainting.

It ended its days shapeless and vast

That terrible, unscrupulous person whose name was "Iskolat".

Virza stuffed the papers into his breast pocket and looked at the audience.

"Hell's shfunk", Austriņš said: "You'll read that tomorrow, Friday evening."

"I would like to knock it on the door of the "Iskolata", the poet said in a mysteriously quiet voice.

"Then I need to type it up." I know where the typewriter is."

By Friday evening, the poem had already been rewritten and was knocked on the door of "Iskolata" in the morning.

It would be hard for the author of the poem to cope if new, important, and unexpected events did not occur.

Page 48

The predictions of the fraternization agitators did not come true. German troops concluded the fraternization with a rapid march along the Vidzeme highways through Cēsis, Valmiera and Valka to Pskov and Narva.

In Valka, this surprise was marked by two huge explosions, from which the house on Semināra Street rose, swayed and sank deeper into the ground. On the side of the station, a white smoky oak tree, like a huge cloud, appeared in the blue sunny sky. A Russian ammunition depot rushed into the air, scattering cannonballs and cartridges for versts and digging a huge hole in the ground, filled with exploded shells, which the Valcēni people collected for flower vases. The Germans confirmed their fraternal entry into Valka by hanging two people on St. John's Church Square near the telegraph poles. The hanged people hung barefoot for three days, because their boots had been stolen on the first night. They were not revolutionaries, not Bolsheviks, but victims whom the leadership of the German conquerors chose to represent the revolution.

The revolution itself, with "Iskolat" and "Iskolastrel", moved eastward and sank into the vastness of Russia.

The house on Seminar Street shook for two days and nights from the wheels of the carts that drove past.

These were the wheels of the departing Russians and the arriving Germans.

The Germans enter Vidzeme

Page 49

The German's nailed boots sounded so terrifying in the streets that people retreated into their rooms and didn't even dare to look out the windows to see what was happening outside. A lull fell over the city.

The old steel grinder on Seminar Street was still grinding his tequilas, because everyday life has little to do with great events. Mechanics are needed in all machines and countries. For the soldiers of every government, something happens that is suitable for a revolver, a sword, or a bayonet, but for the citizens, for saucepans and knives. The master still worked and lived. The profession is not cursed.

Page 50

When the Russian army left, and the smoke from the explosion above the station dispersed, an unusual silence fell. The inhabitants were afraid that the riots and looting would not begin, because Russians who had strayed from their units were still wandering on the roads, they also remained in the city. The last regular Russian units left around breakfast time. However, nothing happened and in the afternoon the Germans marched into Valka, marching in time with the whistle that went ahead of them.

Notices immediately appeared on the walls, prohibiting people from going out in the street in a chair and threatening the death penalty; the notice was signed by the commander-in-chief, Count Kirschbach. A machine gun protruded its nose into the main street. Patrols stood at the corners of the streets with rifles at the ready.

The next day, the commander of the front, Prince Leopold, drove through the city in a car. Back home, the city seemed as dead as after a plague epidemic. Only three days later did the movement begin, but it was accompanied by the shadow of Kirschbach.

A small number of German troops remained in Valka, the majority followed in the footsteps of the Russians. The Germans occupied all of Latvia, including Latgale, as well as Estonia and Lithuania.

Page 51

Life in Valka gradually calmed down and returned to normal. People, unable to do anything social, devoted themselves to their personal lives, which brought more and more worries, there was a shortage of food, it was forbidden to leave the city, and it was impossible to find work. You could already meet acquaintances on the streets: newspapermen, members of the National Council, actors, painters and writers. This bohemia was like the heart of the people, which silently sent life force throughout Latvia. Its activities were reflected in the newspapers. On Saturdays, bohemia would also go to the Ruķeļi house, three versts away, to hang out with the wise owner, bathe in his sauna and drink coffee with cream and sugar, fashionable in peacetime. In those days, it was a pure wedding in Cannes.

Page 52

In the shop, the owner showed off huge cabbage barrels that had once been prepared to feed the army. They were like the towers of Jersika, taller than a hay wagon, but now empty.

During this time, everyone stayed close-knit, feeling that only togetherness could still save, they inspired each other with faith in the future of Latvia and thus stayed above the level, not collapsing into pessimism. The need for togetherness drew the bohemian to Ruķeļi. A lively and believing politician was still there, Skalbe, but a singer full of hope and carefreeness, Antons Austriņš. The owner's own silver laughter and deep bass rang through everything. The diligent hostess quietly flowed from room to room, from house to barn and granary, always with her hands full like a generous autumn. Her house was full of bright thoughts and lively language even when the fires of Valka were already beginning to go out behind the fields.

At that time, the archer Rudainis liked to sit with the ironmaster on Semināra Street, who had been an honest workman all his life. He liked to watch his dexterity and listen to stories about the old days of Valka.

Page 53

The master had a lot to tell, because he was well-read in his book of memories, in which all the people of Valka, whom he had ever known, lived.

The Master spoke about the times when the Relief Society was founded. It was primarily staffed by teachers:

Page 54

Kārlis Gulbis, Matīss and parish employees Īverts, Kārkliņš, student J. Lapiņš, conductor Fr. Pličs, Pavlović brothers. The Relief Society has developed a very active cultural work and has become widely popular. People have visited its events like thirsty people visiting a spring of water. In 1912, T. Zeiferts' lectures on the history of Latvian literature were organized. The lectures were given for ten days, and 200-250 listeners attended them every day. Fričas Bārda's lectures on art were also attended. In 1913 and 1914, large cultural festivals were organized, which lasted three days. A progressive national spirit has taken root in Valka. The progressive spirit of Valka was not socialist, if it could be called leftist, then only leftism in the spirit of Rainis, not purely international.

So the winter passed. The Germans were still in power and were not going to leave. As the ice melted and the streams merged into rivers, Valka Putra Hill reflected the mill pond as it had shone when the half-German grandmothers had come here in the evenings to look at the moon. In the pond, the crescent moon shone like a worn-out battle axe. Already at that time, something was wrong again on the war front.

Following the formation of the idea of Latvia, we must return to the events before the German occupation.

After the Tsar abdicated in March 1917, Latvian nationalists actively began preparing the way for Latvian independence, although internationalists disrupted this work.

Page 55

Valka, bringing together Latvian organizations and the most active workers, was the main initiator and propagandist of the ideas of self-determination and independence of Latvia. The first preparatory work for the organization of Latvia took place here. The first real step in this work was the invitation of the Latvian Central Association, with the signatures of the chairmen Skubiņš and Blūmbergs, to the Latvian parish boards and parish administrations to send delegates to a meeting of rural residents in Valmiera on March 12 and 13 to discuss the unification of Latvia into an administrative unit and the form of administration of this unit. Delegates from Kurzeme among the refugees were also invited to the meeting. The meeting was called the Land Meeting. 440 delegates attended it. The resolution of the Land Meeting demanded: recognition of Vidzeme, Kurzeme and Latgale as one administrative unit with the name – Latvia. It would be an autonomous part of Russia. Latvian language to be used in schools and local governments.

This decision was the first stone in the construction of Latvia. It expressed a mature demand: the laws of revolutionary Russia allowed for talk of autonomy. Now it seems moderate, but at the time such an idea was quite progressive, and as a minimal demand acceptable to wide circles.

The time of German occupation

Page 60.

Just as during the Bolshevik era, elected local governments could not function, everything was determined and managed by the war administration with appointed trusted officials. The German language was hastily introduced into schools. Nothing could be done in public that did not correspond to the intentions of the German high command. The Latvian National Council still had to remain inactive. Its only attempt to show signs of life was two memoranda submitted to the German Chancellor against the cunning policy of the occupation authorities in Latvia and for respecting the Latvian right to self-determination, as provided for in the Brest Peace Treaty. But the memoranda had no echo.

The second work of the National Council was the establishment of the National Theatre in Valka, which had a certain cultural and political significance during this sad time – to keep the Latvian intelligentsia and people who remained in Valka together, to gather together the scattered family of actors, and to do something in general.

Page 61

At that time, the rusty beard of Andrieva Niedra also appeared on the streets of Valka. He chatted, asked questions, inquired about something in the National Council, sensed something, expected something, and then disappeared like a dream. What this dream meant, no one could guess at the time. The Central Association and “Konzums” could only work on food deliveries.

The only breath of life for Latvians at that time was the same “Līdums”, which, after the Bolsheviks’ denial, tried to be published as a newspaper of the Peasants’ Union in Moscow (under the name “Gaisma”) and in Pēterpils (“Tauta”), and whose publication in Valka was permitted by the German headquarters under strict conditions. The content of the newspaper was filtered by wartime censorship through a fine sieve that did not even let the word Latvia through. Editor Nonācis had to use great diplomatic skills to finally allow this word. He was at war with censorship with every issue. And yet, in “Līdums”, public opinion could express itself to some extent, it could be woven into information, fiction, where it was difficult for the censor’s eye to perceive it. A literary magazine “Jaunā Latvija” was also published, edited by Kārlis Skalbe and Artūrs Kroders. Writers had a say in it, and this showed that writing had not yet died out. National thought also lingered there.

Page 62

The old party members were even allowed to organize writers' evenings in Valka, of course, with censorship.

Proclamation of Latvia

Page 69.

There were three strong political groups, whose separate views were not easy to reconcile. The Farmers' Union with its center in Valka, the Democratic Bloc in Riga, and the Social Democrats. Then Kārlis Ulmanis, who was the founder and leader of the Farmers' Union, but who had also participated in the Democratic Bloc throughout the occupation, used his diplomatic and political skills to resolve the differences. After negotiations in Riga with the Democratic Bloc, he immediately traveled to Valka, where he convened a full meeting of the Farmers' Union, also attended by the rural branches.

The meeting was held on November 15, 1918. It took place in the editorial offices of “Līdumas”. It was quite large, as representatives also came from the countryside. Among the leaders of the farmers' union were Kārlis Ulmanis, Miķelis Valters, V. Gulbis, P. Siecinieks, V. Skubiņš, editor O. Nonācs, etc. The meeting was opened by Kārlis Ulmanis, proving in a longer speech that the final moment had come to proclaim the independence of the state of Latvia and for Latvians to take control of the government in their own hands.

The unarmed people

Page 99.

Not even a month had passed since Konzums, “Līdums” and the members of the People’s Council left Valka when warning news arrived about the Red Army’s invasion of Estonia and its advance on Valka. There was not a single armed person in Valka, not a single revolver that could rise up against the invaders, because all weapons had to be returned to the German commandant’s office at the appropriate time.

As soon as the Germans were leaving, local public workers gathered at the Valka Credit Union to discuss what to do for security and how to stand against the Bolsheviks. Dr. Lībietis suggested negotiating with the Estonians on this matter.

Page 100

After the Germans left, the public workers gathered again at the county council to discuss organizing the partisans. Again, the issue of weapons remained unresolved.

Northern Latvia had no choice but to surrender to fate. And that fate was the rule of the Bolsheviks. The Bolsheviks entered Valka on December 18th.

In Valka, the Bolsheviks immediately set about organizing the administration. They placed their own people in the city council, appointed commissars, and established tribunals, the foundation of their power.

Page 101

Schools were also reorganized according to their own rules. Social life came to a complete standstill, and the same situation as during the German occupation set in. Former societies were closed to open communist propaganda clubs.

The Bolsheviks did themselves a lot of harm with the terror directed against unarmed residents. The horror of the death penalty walked the streets. The number of people shot in Valka is estimated at 130 people in one month. Fifty people, well-known people from Valka and the surrounding area, were wiped out with a machine gun in one night near the Lugaži cemetery. They also shot in the gravel pits near the Zīle Krōgus road and in the current fraternal cemetery, they shot at the decision of the tribunal and also without any trial people who, even from the Bolsheviks' point of view, were not guilty. This most of all angered the residents against the new regime.

Page 103

The time of the Lielinieki government in Valka lasted 1 month and 13 days (from December 18, 1918 to February 1, 1919).

Page 104

On February 1, Estonian and Finnish troops entered Valka. During the same march, the Latvian parishes surrounding Valka were also liberated.

Valka had just been taken; the next day the Estonian commandant convened a meeting of the city council, chaired by the council chairman, teacher Bricmanis. The meeting discussed Latvian cooperation with the Estonians, but it did not progress from verdicts to action. Bricmanis was to appear before the Finnish commander Kalma the next day. He explained that, based on the information he had gathered, he had recognized the functioning of the council in its current composition as impossible, namely, that the Latvian majority in the council had been obtained illegally through the participation of refugees from Kurzeme in the council elections, and that the refugees were not permanent residents of Valka.

Page 105

The council's activities were interrupted during the serious period by the old dispute between Estonians and Latvians over dominance in Valka. Only Estonian councilors were allowed to work, who then divided the school buildings and established a school commission, to which the Latvians invited the principal Stipra, teacher Bricmanis, and teacher Brokas.

This caused confusion in Latvian society.

Then, to encourage Latvians to become active, several meetings of Latvian public organizations were held, in which representatives participated: from the Vidzeme Land Council, the Valka City Board, the Valka Social Society, the Valka Aid Society, from the credit union at the social society, from the boards of the liberated seven parishes and from the Northern Latvia Red Cross Society. The most active employees of the meeting were: Dr. J. Lībietis, Jānis Ķimens, teacher Kārlis Gulbis, teacher Bricmanis, teacher Matīss, director J. Stiprais, farmer Šmits, Birkerts, Ūdris and P. Indus.

Page 106

The leaders nominated at the Valka organization meetings decided to turn to the local Estonian-Finnish military commander Kalma for permission to organize Latvian troops from the residents of the liberated and future liberated Latvian regions. Dr. Jānis Lībieti and farmer and land council member Otto Hasmani were sent as delegates to Kalma.

In the first conversation, Kalms was reserved and cool. He said that according to his information, all Latvians were Bolshevist. Kalms did not give the delegation a definite answer, but ordered them to come with a definite proposal.

A meeting of public workers met again to discuss and adopt the proposed draft and decided that it was necessary to first find out how many men could be called up for military service in the liberated area, and therefore an order should be issued to register those who were called up. The order was issued on behalf of the Land Council elected during Kerensky's time, which the city commandant Kornels had already renewed on February 13; its board members were: teacher Ernests Nagobads, the head of the Lugaži parish Pauls Indus and farmer Otto Hasmanis; commandant Kornels assigned premises to the Land Council board in the Valka district office at Rīgas street No. 9 and issued 2,000 Estonian marks for organizing the work. It was the first official Latvian institution that could be relied on for public work.

Page 107

As for who should sign the registration order, the meeting agreed that it should be signed by persons with connections to previous non-big government administrations, so that the order would have the necessary respect among the population and a legal basis. The order was signed by county board member Otto Hasmanis, which gave the order a certain legitimacy and trust.

The order was as follows:

Paul.

The Board of the Valka District Land Council, by order of the Estonian Provisional Government, which was made in accordance with the Latvian Provisional Government, orders all residents of the city of Valka, suburbs and Valka parish to come to Valka, Rīgas Street No. 9, on February 18, 1919 at 10 a.m. without fail:

Latvian officers up to 50 years of age;

Latvian military doctors up to 60 years of age;

for military officials up to 50 years of age;

Latvian paramedics up to 45 years of age;

Latvian non-commissioned officers, as well as graduates of non-commissioned officer training teams up to 35 years old.

All five categories of soldiers living in the Valka district, up to the same age, must arrive at Valka, Rīgas Street 9, on February 19, 1919 at 10 a.m.

Everyone should be warm and dressed in military uniform if possible, and bring food for about 5 days.

Failure to comply with this order will result in the perpetrators being held accountable by a court martial.

Wear,

Chairman of the Board

O. Hasmanis

Page 108

The second command was:

Paul.

The Board of the Valka County Land Council hereby orders all male residents of Latvian nationality living in the city of Valka and its suburbs, who were born between 1869 and 1902, inclusive, to appear without fail for registration.

Registration will take place in Valka, Rīgas Street No. 9, on February 21 and 22, 1919, from 10 a.m. to 12 p.m. and from 2 p.m. to 4 p.m. Railway and postal employees are exempt from registration.

In case of failure to comply with this order, the perpetrators will be held accountable by a rural court-martial.

Wear,

Chairman of the Board

O. Hasmanis

The same delegates went to Colonel Kalms with the proposal a second time, and he allowed registration. The registration order was posted on poles and sent to the parishes.

Further negotiations about full mobilization with Colonel Kalm were also conducted by Dr. Lībietis and Otto Hasmanis. A significant conversation took place between Dr. Lībietis and Otto Hasmanis and Kalm. When the Latvian delegates were talking about obtaining weapons, Kalms invited a gentleman into his office, whom he introduced as a magister.

Page 109

The colonel and the scientist spoke in Finnish for a moment and pointed to something on the Latvia-Estonia map. It was clear that he was talking about the Latvia-Estonia border. After a longer discussion with the scientist, Kalms turned to the delegates with the question: “Where is the border between Latvia and Estonia?”

Dr. Lībietis replied that according to the 1917 referendum, Valka, Valka parish, Liel – Lugaži, Pedele, Ērģemes, Kāģeri and Cori parishes belong to Latvia.

After this explanation, Kalms spoke with the scientist again. Then he told Lībietis that this was not true. The border was located completely elsewhere, more to the south.

“Whoever touches this border will have to deal with this,” Kalms raised his revolver. Dr. Lībietis reprimanded him, saying that he had no authority to decide on the border, but that he had only mentioned the outcome of the 1917 vote.

Kalms calmed down, but did not give any answers about providing weapons and permission for mobilization.

Another time, the same Kalms showed Hasmanis a map on which the Estonian-Latvian border was marked with a red stripe along the Salaca River, across the Seda to the Riga highway at the Vēžu Krogus Seda bridge, and from there along the Gauja to the old ethnographic border.

Thus, Estonians were already concerned about the border issue and the old Estonian-Latvian rivalry for cultural and economic dominance in Valka and its surroundings.

Page 110

Kalm's behavior made Latvians worry about their position not only in relation to the Bolsheviks, but also in relation to the Estonians.

Despite the lack of instructions and information from the Provisional Government and the fact that no response had been received from the Estonians about the provision of weapons, Latvian public organizations began to work energetically to prepare for mobilization so that the Estonians would not receive all the initiative. Seven Latvian parishes were already free from the Bolsheviks: Valkas, Kāģeri, Lugaži, Liel-Lugaži, Coru, and parts of Ērģeme and Pedele. Something could already be done here.

Latvians decided to stand independently on their small remaining territory and begin the fight for their country.

Page 111

Northern Latvia, Valka, the cradle of national thought, was a good place for such a goal. And on February 3, 1919, the head of government Ulmanis in Tallinn agreed with the head of the Estonian government on the organization of Latvian troops in Northern Latvia. Already on February 3, the Provisional Government appointed engineer Marks Gailītē as its plenipotentiary for civil affairs in Northern Latvia, captain Jorģis Zemitāns as the commander-in-chief of the Northern Latvian troops, J. Ramāns as the plenipotentiary in Tallinn, and lieutenant Lauri as the commandant of Valka.

On February 18, M. Gailītis, Lieutenant Lauris, Colonel Jansons, Robežnieks, and other representatives of the troops arrived in Valka, which relieved local public officials of the responsibility for mobilization and civil administration.

Page 112

Regarding the mobilization in Valka and Rūjiena, an employee of this era writes that it went well and in high spirits, many volunteers arrived, many expressed their readiness to join the army with horses and carriages. Residents donated clothes, bicycles, motorcycles and other useful things for the troops. Faith in the Latvian state and the strength of the army increased.

To inform the population about the events and the government's actions in Valka, the newspaper "Jaunā Dzīve" began to be published, at the same rapid time, on February 20. The newspaper published 24 issues, it stopped on April 17, when the editor of the popular "Līduma" in Valka, O. Nonāka, was preparing to publish the newspaper "Tautas Balss". "Jaunā Dzīve" was published at the expense of Valka's public workers. Its editor was the teacher K. Gulbis and co-editor Jānis Porietis.

Public enthusiasm

Page 113.

Public work in Valka called from all sides. Public organizations and their employees, as well as the incomplete Land Council, could not successfully accomplish all this, therefore the Northern Latvian Red Cross Society was founded, which would provide for the Latvian troops and the population physically and morally. Dr. Jānis Lībieti was elected chairman of the society, his members were Mrs. Eleonora Jansona and Paula Skrīveri, the secretary was Jānis Dzirkalis, the treasurer was Jānis Stiprais, his member was Pēteris Pakalns, the foreman was Jānis Ķimens, all of whom undertook to work without remuneration.

The Red Cross first focused its attention on starving and needy children, providing them with food and clothing. There were many to feed and clothe, but there was a shortage of funds.

The first task of the association was to raise funds. The amount donated among themselves was too small to carry out the extensive work, so the association's board organized open days of fundraising on March 16 and 17, which yielded more substantial funds.

Page 114

The association appealed to the peasants to donate products, because they could not buy anything at the market, it was empty, and to the townspeople to give money. The food situation in Valka was very difficult. In the autumn of 1918, the grain from the Valka district was requisitioned by the army. During the occupation, it was seized by the Germans, and during the Bolshevik period, the remains were fished out by the Red Army. Thus, the city of Valka and its surroundings were emptied. The city grocery store sold residents 2 pounds of oatmeal and 2 pounds of marmalade per person, but that was all.

At first, the Red Cross appeal had little success among the peasants. Later, the Red Cross became a center around which everyone who cared about Latvia's independence united. The ladies of Valka participated especially actively, coming to the aid with their handicrafts.

The association opened a soup kitchen in mid-March, serving 320-400 lunches with one quarter of a loaf of bread per person every day.

Page 115

If milk came in as donations, it was distributed to the children. The kitchen provided great support to the residents and their children who were in need and starving at that time.

For the troops, the Red Cross was not only a sanitary institution, but also a quartermaster's office. A military hospital was established in Valka, on Aleksandra Street, where two doctors worked at first, J. Lībietis and Barts, later also Jaunzems and Daņiļevskis, 2 sisters of mercy (Vīns and Purgale, later also Ede Rudzīte), several nurses, a pharmacy manager and a farm manager. 130 beds were set up for the soldiers. The society delivered medical and sanitary supplies, medicines, linen, clothing, boots, self-made paramedic and cartridge bags, stretchers, soap, etc. to the front. According to a list, the following items were received as donations and sent to the front for soldiers or used for hospital equipment: 53 beds, 70 bed bags, 191 sheets, 58 bed blankets, 46 pillows, 142 pillowcases, 283 towels, 25 pairs of gloves, 49 pairs of socks, various kitchen products, dishes and other items.

From February to August, the Red Cross hospital was privately supplied with linen, food, and medical supplies. It was only in August that the state provided the first aid.

Page 116

Other funds were raised through events, movie screenings, and a cash lottery.

At the suggestion of Dr. Lībietis, the county council decided to organize the production of cartridge bags for the army in the parishes. Each household must produce two cartridge bags.

Bags were made from canvas. Sanitary bags were also made.

The Red Cross took care of setting up the hospital long before the Latvian units were at the front. When the Latvian fighting began at the front, an average of 70 sick and wounded soldiers were lying in the hospital every day.

Written by: Aija Priedīte, chief keeper of the Valka Museum of Local Lore

Ādolfs Erss. Vidzeme in the freedom struggle, Riga, 1935.

Related timeline

Related topics

Related objects

Monument "Dedication to the Latvian Provisional National Council"

The monument “Dedication to the Latvian Provisional National Council” is located in Valka at the intersection of Rīgas and Raina streets (address Raina street 9A).

The monument was unveiled on December 2, 2017, as part of Latvia's centennial program, in honor of the meeting of the Latvian Provisional National Council in 1917.

The author of the ensemble idea is the sculptor Arta Dumpe, the stonemason – Ivars Feldbergs, the architectural planning was carried out by SIA "Architectural Office Vecumnieks & Bērziņi".

The base of the monument is formed by a large millstone – like a circle of life, time and events. The names of the LPNP board members are engraved on its sides. From the millstone, like the paths of fate, three regions – Vidzeme, Kurzeme and Latgale with their historical coats of arms – rise up into the sky. The composition is concluded by the Bethlehem star, which transforms into the sun of the new Latvian state. Latvian poet, prose writer and politician Kārlis Skalbe /1879-1945/ wrote: “Latvia also had its own Bethlehem, little poor Valka...”.

The monument to the Latvian Provisional National Council is a kind of debt repayment to the people who, risking their lives in Valka in 1917, guided by ideals, laid the foundations of the Latvian state in a virtually impossible situation.

At that time, Valka was the city with the largest Latvian population in the territory not yet occupied by Germany. After the fall of Riga, it became the center of Latvian social, political and cultural life. Those who were united by the desire to implement the right of self-determination of the Latvian nation gathered here. From November 29 to December 2, 1917 (according to the new style), the 1st session of the Latvian Provisional National Council was held in the Valka City Hall (now the building at Kesk Street No. 11 in Valga), in which representatives of almost all the most influential Latvian public organizations and political parties participated. For the first time, they officially declared the goal of their activities - the creation of an independent national state, and adopted a declaration on the creation of a united and autonomous Latvia in the Latvian districts of Vidzeme, Kurzeme and Latgale.

Exhibition “Valka - the Cradle of Latvia’s Independence”

The Valka Local History Museum is located in Valka, on the right side of Rīgas street, in the historical building of the Vidzeme Parish School Teacher Training Seminary. From 1853 to 1890, the building was home to the Vidzeme Parish School Teacher Training Seminary. Until 1881, it was led by Jānis Cimze, a teacher and founder of Latvian choir culture. After the School Teacher Training Seminary was closed, the building served various educational, cultural and household needs for 80 years. The building has been home to the Valka Local History Museum since 1970. The museum’s permanent exhibit – ‘Valka, the Cradle of Latvia’s Independence’ – has been set up as a story about social and political events in Valka from 1914 to 1920 when Latvia became an independent state. The exhibit reflects the preparation leading up to the establishment of the Latvian state and the formation of the North Latvian Brigade in Valka. Through four senses, namely, the Road, the Council, the Headquarters and the Home, the exhibit focuses on topics related to the city of Valka, refugees, the founding of the Latvian Farmers’ Union (1917), the

Latvian Provisional National Council (1917), the Latvian Provisional National Theatre (1918), the Provisional Government of Soviet Latvia known as the Iskolat, the North Latvian Brigade (1919) and General Pēteris Radziņš. In addition to the traditional ways of showcasing collections, the exhibit makes use of interactive multimedia solutions.

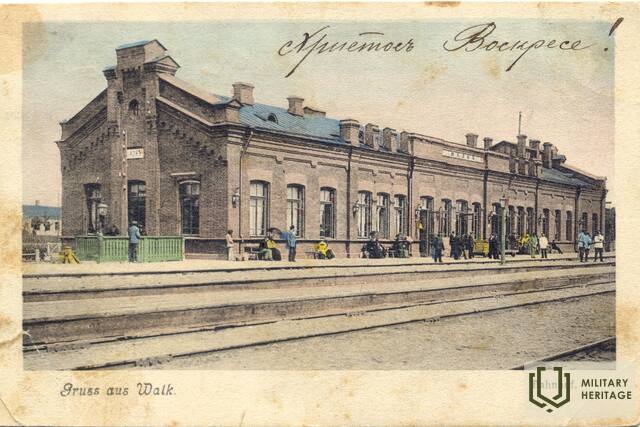

Valga railway station built by German prisoners of war

The main building of Valga railway station (Leningrad Transport Planning Office, architect: Viktor Tsipulin) was completed in 1949. It is an elongated two-storey structure with an avant-corps and a hipped roof, its architectural showpiece being its seven-storey square tower. It is one of the best and most remarkable examples of Stalinist architecture in Estonia. Its original state having been so well preserved further elevates its significance. The railway station was built shortly after World War II in place of a building from the imperial era that Soviet bombing had razed to the ground. Since German prisoners of war were detained in Valga, it is plausible that they were used to construct it.