19-year-old Alfons Wolgemuth's story about the reconnaissance battle on February 17, 1945 near Priekule

Alfons Volgemuth was a 19-year-old boy, a radio operator and served in the army of Nazi Germany.

"No one has come back from this operation and it is not known if there are any survivors. I myself took part in that war as a 19-year-old radio operator and I am one of the 2, later 3 survivors who were taken prisoner by the Russians. I want to reflect the events from my own experience."

On February 16th we were at the edge of a forest north of Priekule. We received an order to be ready for battle at 10:00 PM at the former Priekule manor house. We checked the radio and in the evening went to the indicated place, where about 200 grenadiers from II/GR426 and 20 tanks had already gathered.

We talked quietly. We realized that we would go into battle with tanks. Franci and I sat on the ground near a big tree. It was freezing, but not too cold. While waiting for the order to leave, we talked about what might await us.

Up until now we had been directing artillery fire by radio, but now it seemed that we would have to take part in the battle. Francis told me to stay with him the whole time. And then the tanks began to roar, each of them taking about 10 men, who sat up on the platform. The three of us sat on the front tank, behind which everyone else was moving southwest. It was around 2:00 am on February 17, 1945. We were moving across the railway, along the forest along the road in a southwest direction. The fire was not too intense. At first the Russians were shooting only with small arms, then with anti-tank guns. We remained unharmed, only a fragment of a grenade tore off the heel of Francis's boot.

When we had driven about 3-4 km, the tanks stopped. We jumped off them. Bullets were flying around. The shots were coming from a hill about 100 m to the left of the road, from some country houses. A not very deep ditch ran along the road, we jumped into it. The tanks turned around and drove away. In the darkness we could see a small barn, from which 2 Russian soldiers ran out. Obviously, without weapons. One of them looked wounded.

Francis shouted: “Stop! Hands up!” Both soldiers raised their hands in the air. Surrendered. We ran into the barn. This must have been our goal, where the commander had ordered us to take up combat positions. Shortly before this moment, the area had been completely in German hands. The barn, about 6x6 m. At the bottom was a basement with a deep entrance, in which there were three compartments separated by boards. In the first, the largest, there was a large table with telephones. In the far compartment, which were two-story bunks-mermaids, we imprisoned the two Russian prisoners. We arranged the transmitters and antennas.

We tried to contact our battery, but we didn't get any answer. We couldn't establish contact later either. There was noise outside. Our men were attacking the Russian positions there. We sent a report about the situation, but we didn't get a response. The grenadiers took the Russian positions, only with very heavy losses. The orderlies brought 2 wounded to our basement and took care of them.

During one of the respites, I let the wounded Russian out of the precinct. He had a gunshot wound to the chest, but he was breathing just fine. I bandaged him, gave them both a piece of bread and a cigarette.

As day broke, the medics pulled out another wounded man. He lay about 100 m from us, groaning heavily. For a while, no one fired. Then the fighting resumed. It seemed that the Russians had received reinforcements and were attacking again.

The Russians began to use heavy weapons. Some grenadiers reached us and said that they could no longer hold this position, because most of us soldiers and officers had already fallen. There was nothing left but to retreat. There were 14 soldiers and three wounded in the basement. No officers. One of the soldiers suggested running across an open field about 250 m wide to the edge of the forest. This could have been successful if we had fire protection. Therefore, it was decided; 3 of us would stay and continuously fire at the Russians to ensure the rest had the opportunity to retreat to the nearby forest.

To stay in the basement to provide covering fire, they chose me, another 19-year-old guy, and an older grenadier with a head wound. At around 10:00 on the morning of February 17, the others left the basement of the country house. The three of us fired at the Russian positions as hard as we could. The others ran away in the same way - as hard as we could. One of the runners fell and remained lying there. I think it was a medic. The others reached the edge of the forest, but there they were met by Russian fire. I heard loud screams. I thought I heard the voice of my friend Franz Kellenter among them. Then everything fell silent. Silence fell on us too. A terrible silence.

We realized that we would be captured or shot. The wounded groaned quietly. Their fate was also unknown. The door to the outside remained open. I didn't know whether to go out or stay here – in the basement.

Then suddenly a German tank appeared on the road. It stopped. It did not fire and was not fired upon. Therefore we decided that it was a Russian tank. Then it turned sharply and drove away. A few minutes later, I heard quiet noises outside, as if someone was carefully walking on the rubble. I looked at the open cellar door and saw a bearded face with searching eyes. Then those eyes saw me! The man turned sharply and disappeared. A few minutes later we heard loud voices outside. A hand grenade fell at the entrance to the cellar and exploded loudly. Some of the shrapnel hit the wounded, and they screamed loudly.

Well, our Russian prisoners were also shouting something to their comrades. We let them out. After a while, we were also called to come out with our hands raised. In front of us stood a Soviet army sergeant with a pistol in his hand and a few more Russian soldiers. The wounded in the basement were moaning and screaming. The sergeant went down. We heard shots. Then everything fell silent.

The sergeant came up to me and took aim. Then both of our prisoners began to speak, pointing in our direction. The sergeant lowered his gun. Our pockets were searched. My crown of roses was thrown to the ground. More Russian soldiers came up. We were taken to the dressing station. On the way, we had to carry a stretcher with a seriously wounded soldier. His leg had been torn off. It was only held on by a small piece of tissue. As we were carrying him across the field, shooting started nearby. As usual, we fell to the ground. The wounded Russian on the stretcher screamed in pain. He kept repeating: “Tikhonko, tikhonko!” I didn’t know what it meant then. Later, when I learned a little Russian, I understood what this word meant.

So we reached the Russian headquarters in a country house. There we were interrogated one by one. Threatening me with hanging (showing me a rope), I was ordered to show the positions of our battery on a map. It was a Russian map. I said that I couldn't read anything on it. Then they brought me a German map. There I saw the road we took from Paplak to Priekule. I pointed at the map with my finger and pointed to a field about 200 m to the left of the road. In fact, our positions were on the right side of the road, behind a forest.

Later, after the capitulation, I met a sergeant major from our unit in the prisoner of war camp. He was pleasantly surprised to meet me. He told me that no one had returned from our operation on February 17th and that there had been heavy shelling that day near our positions, on the left side of the road. However, there were no serious losses for our troops.

The third of us, the senior grenadier with a head wound, was completely disoriented. Apparently, under the influence of the death of his comrades. A Russian went with him behind the barn. A shot rang out from there, and the Russian returned. Alone. So we were left alone. In the evening I was taken to two higher-ranking Russian officers. One of them spoke German. He talked to me in a very humane manner. By the way, he asked me about my attitude to the war. I told him about my life and how the Nazi government had dealt with my family. My father was a police officer;

He was fired from his job in 1934 for refusing to join the SS. His father was killed in France in 1944. After interrogation, we were given millet porridge, bread, and water.

We spent the night together with several Russian soldiers in one room. We were allowed to sleep under the beds on the floor. The next day, accompanied by several soldiers, we were taken by truck to the prisoner collection point in a shed in the Skoda area. There were about 10 of us there. None of our combat group was among them. There probably weren't any more prisoners either. About 200 men participated in our operation. If no one was here, just the two of us, then everyone must have fallen. The meaning and purpose of this operation are described in the divisional chronicle. The strategy and execution are incomprehensible to me, as a strategy amateur. I also don't understand what was paid for with 200 lives.

This was followed by two years of Russian captivity in Riga: a camp in Kaiserwalde, work clearing rubble in the city and in Olaine – a peat camp south of the port of Riga. Peat work lasted all summer. Our saying: “Water from above (rain), water from below (swamp), water inside (in the legs from hunger) – that Olaine suffering.” By autumn I had already lost 50 kg. Then I was transferred to Northern Estonia: Kotla-Järve, Jove, Tammika – stone quarries, forest work, construction, etc.

In 1947, I was released from the camp on suspicion of having tuberculosis.

I found my mother, who had been expelled from East Prussia, in Westphalia.

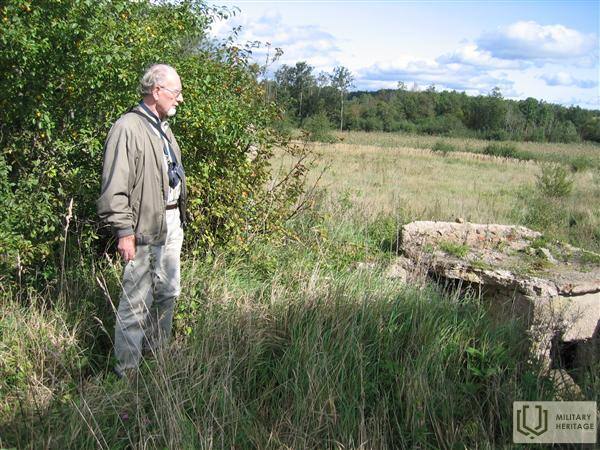

In 2008, I visited Latvia with my son and a friend's family. In the vicinity of Priekule, we were looking for the fateful place where most of our comrades died and where I myself was captured. With great difficulty, we managed to find it about 7 km southwest of Priekule. The ruins of a basement, an uninhabited country house - everything overgrown with bushes. It was a strong emotion, standing in the same place where a gun was aimed at me. I managed to survive!

There was no one to ask if there was a German soldiers' cemetery nearby. We visited the Russian soldiers' cemetery south of Priekule. There are more than 20,000 fallen there and a very expressive monument. In Russia, too, mothers, wives and children cried for their sons, husbands and fathers. A serious warning so that nothing like this will ever happen again.

www.kurland-kessel.de

Your comments

Thank you for this report. It touches me deeply, as my grandfather also died in this battle (on February 17 or 18). Unfortunately, we don't know much about it, and he was probably never found, so it's especially interesting to learn about those days this way.

Related timeline

Related topics

Related objects

Priekule Memorial Ensemble of Warrior’s Cemetery

The Priekule Memorial Ensemble of Warrior’s Cemetery is on the Liepāja-Priekule-Skoda road and is the largest burial site of Soviet soldiers of World War II in the Baltics. More than 23,000 Soviet soldiers are buried here. Operation Priekule was one of the fiercest battles in Kurzeme Fortress that took place from October 1944 to 21 February 1945. The Battle of Priekule in February 1945 lasted seven days and nights without interruption and had a lot of casualties on both sides. Until Priekule Warrior’s Cemetery was transformed into a memorial, the last monument of the outstanding Latvian sculptor K. Zāle (1888-1942) was located here to commemorate the independence battles in Aloja. Between 1974 and 1984, the 8 ha Priekule Warrior’s Cemetery was transformed into a memorial ensemble dedicated to those who fell in World War II. It was designed by the sculptor P. Zaļkalne, architects A. Zoldners and E. Salguss, and the dendrologist A. Lasis.

The centre of the memorial holds a 12 m tall statue called the ‘Motherland’, and names of the fallen are engraved on granite slabs. Until Latvia regained its independence, the Victory Day was widely celebrated every year on May 9.

This was an interesting story to read about the experience of this man. I wish the website had more of those from both sides of the men who fought in the Kurzeme area.